Mary Quant did not invent the miniskirt. She didn’t conceive it, nor did she create it. Nor can she solely be credited with popularizing it. Instead, what Mary Quant did for the miniskirt was something much greater, even revolutionary: she gave it a commercial platform. André Courrèges, who always claimed authorship of the garment, scorned Quant for her daring entrepreneurial feat, likening her to Prometheus, seizing the fire of high fashion salons to ignite the mass market. “Fashion is something inherent to everyone and should not depend solely on beauty, fabric cost, and manual labor. It has to be mass-produced,” declared the British designer.

Thus began the true modern history of dressing. Early reports of skirts above the knee were not scandalous. Even Cristóbal Balenciaga introduced them in some versions of his sack dress in 1957, emphasizing proportions that obscured the body. Yves Saint Laurent also experimented with them, more as a promise than anything concrete, in his first collection for Dior, the spring-summer 1958 line that reimagined the 1955 A-line. Encouraged by the magazines of the time, that light, rejuvenating silhouette, which allowed for movement once again, quickly escalated, mass-produced by textile manufacturers and merchants with or without Parisian licenses, supplying stores and department stores. But the vicious cycle of the system, the class-based transmission of style, remained unchanged.

“It was wrong back then that fashion had only one roadmap: it was created for a minority,” admitted Quant in 1988, in conversation with writer Joel Lobenthal, author of “Radical Rags: Fashion of the Sixties.” “What I wanted was to design for women who had a job and a fantasy of life where those jobs mattered.” The economic and social emancipation through fashion, that was the issue. It so happened that, starting from 1950, youth emerged as an unprecedented force for change. In Britain, boys and girls aged 16 to 22 stormed into the labor market, with salaries that by 1960 doubled those of adults. “Their earnings have increased by 50 percent and their real discretionary spending is probably up by 100 percent,” noted sociologist Mark Abrams, the father of current market studies and a pioneer in identifying teenagers as a demographic segment with their own culture and consumption interests (“distinctive adolescent spending with distinctive adolescent ends in a distinctive adolescent world”). Without burdens or responsibilities, the youth splurged on music, bars, and clothes, lots of clothes. Not just any clothes, of course. Certainly not those sold by the chains and department stores where their parents shopped. The post-World War II generation was indeed the first to refuse to resemble their elders, especially in matters of dress. “Couture is for kept [women],” mocked Barbara Hulanicki, Quant’s contemporary and founder of what would become the seminal stylistic mecca of Swinging London, the Biba boutique, which started as an illustrator in various newspapers in the late fifties, copying Parisian figurines, designed to make anyone feel inferior.

Through the Youth Commission program, the Labour government also took the initiative to broaden the horizons of the island’s youth with a policy of economic aid that overflowed the faculties and art schools with students from humble backgrounds. The fashion degree at the Royal College of Art—the first to be taught at the University of London, developed in 1948 by Madge Garland, a journalist and promoter of the London Fashion Group, predecessor of the British Fashion Council—was a hit. “We were trained to observe, explore, and enjoy the work. We felt that when we finished, we could do anything, without restrictions,” recalled designer Sally Tuffin, half of the Foale And Tuffin duo, another label to consider in the evolution not only of the miniskirt but of the shift in early-sixties clothing led by women. Zandra Rhodes, Moya Bowler, Janice Wainwright, Bill Gibb, and Ossie Clark were also students. Quant’s parents didn’t allow her to study design, but the scholarship she obtained to study drawing at Goldsmiths College had the same effect.

The daughter of schoolteachers, descendants of Welsh miners relocated to the outskirts of the capital in search of a better life, Barbara Mary Quant exemplified the jovial interclass uproar of the moment herself. At art school, she met her future partner and husband, Alexander Plunket Greene, with quite the pedigree: grandson of the legendary Irish baritone Henry Plunket Greene and the British aristocrat Gwendoline Maud Parry, son of the motorcycle racer, jazz musician, and writer Richard Plunket Greene, a gem among the Bright Young Things whose escapades filled the pages of London tabloids in the twenties (a close family friend, writer Evelyn Waugh, drew inspiration from him and his siblings, David and Olivia, to create characters in “Vile Bodies” and “Brideshead Revisited”). They arrived in Chelsea still as lovers, which in 1955, at the dawn of the youthquake, was no ordinary neighborhood either, a hotbed of musicians, artists, filmmakers, and society pups pretending to be beatniks in cafes (espresso bars) and clothing stores. In November, they opened a restaurant, Alexander’s, and a boutique, Bazaar, in the building that Plunket Greene and his friend Archie McNair, a lawyer turned photographer, had acquired on King’s Road. The bistro was a failure; the store, a success that would irreversibly change the model of commerce and what we now call the shopping experience.

Since Courrèges put her in a spot by labeling her as a commercial agent, not a creative one, Quant never tired of repeating that the miniskirt was nothing more than the product of her time. Of her contemporaries. “I thought my skirts were short, but the girls who came to the store asked me to raise the hem even more,” she recounted. The continuous parade of mannequins in the shop window, rock blasting from the stereo, free drinks, and extended opening hours into the night did the rest. In this case, there is evidence that questions the Frenchman’s claim: the designer officially launched the garment for fashion in his haute couture collection presented in April 1964, but the Victoria & Albert Museum in London preserves a minidress from Quant’s diffusion line, the more economical Ginger Group, dated that same year. The London museum, which holds the largest archive of the designer, also has evidence that skirts and dresses were already being sold at Bazaar with hemlines just above the knee in 1958. At home, buyers would shorten them more and more. “It’s difficult to find originals from the early sixties without alterations,” says Nigel Bamforth, curator at the V&A who worked for the brand as production director for almost two decades. “Mary’s creations were decisive for the introduction of the miniskirt into the mass market. They went against the norm, and for girls, it meant they didn’t have to look like their mothers,” he concludes.

“It was the Chelsea girl who established that this second half of the twentieth century belongs to youth. Young people with their own ideas. Committed. Without prejudices. They represent the new attitude of today’s Great Britain, a classless spirit,” the designer explained

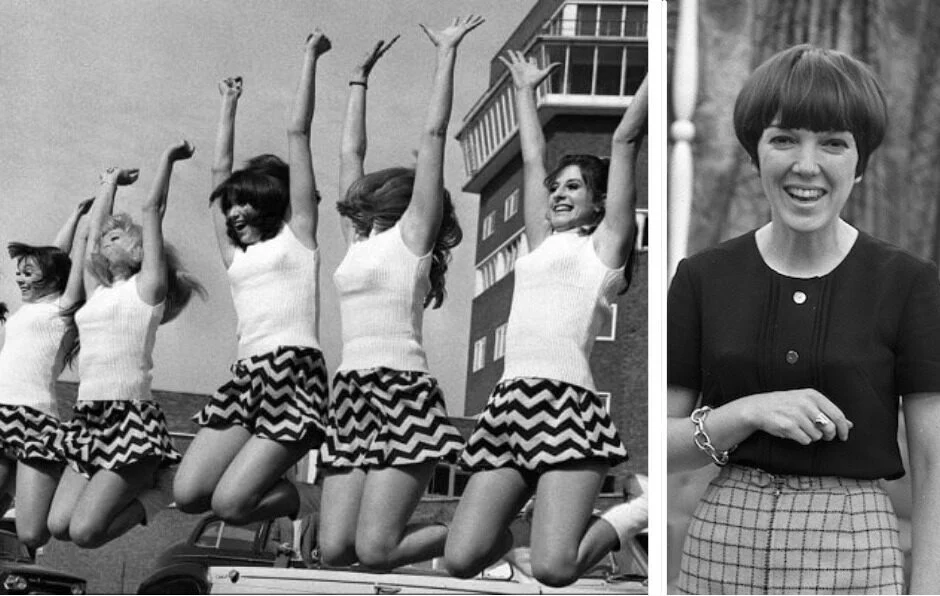

in “Quant by Quant,” her precocious autobiography published in 1966. She was around 36 then, and with the newly launched cosmetic line, she had already done it all. Owner of three stores (King’s Road was followed by one in Knightbridge and another in New Bond Street), with two lucrative licensing contracts to produce and sell her collections at low prices in the United States, her business volume approached 20 million euros (almost 200 million at current exchange rates, according to accumulated inflation), a staggering amount for the time that, to the benefit of her country’s coffers, earned her the Order of the British Empire. A year later, Time magazine headlined: “The miniskirt is here to stay,” noting that “since its appearance three years ago in small and unconventional boutiques and dark nightclubs, it has reached campuses, offices, avenues, and any place where youth chooses to defiantly show its colors.” But, surprise, the one who appeared on the cover alongside two miniskirted models was the American designer Rudi Gernreich.

The chapter on men trying to capitalize on the origin of the miniskirt is worth considering in this story. Besides Courrèges, in Paris, the visionary Pierre Cardin launched his Cosmocorps line in the same grace year of 1964, which included the first version of the succinct Target dress, the white minidress with the red, yellow, and black bullseye (although the king of licenses never got involved in the controversial conception). But in London, John Bates also took the credit, defended by the highly influential Marit Allen, Vogue’s fashion editor who signed the Young Idea section. Under the commercial name Jean Varon, his mini dresses with simple geometric lines were bestsellers at Wallis, a popular retail chain licensed to copy those Chanel and Dior models scorned by the new generations as early as 1960. And then there was the ya-ya skirt, a flared skirt with a twist name raised up to 15 cm above the knee, to be worn with a petticoat, attributed to the anonymous sales manager of an Oxford Street store and even crossed the Atlantic in the summer of 1960. “This is more than just a toast to the sun. This fashion shows that women are seeking a matriarchal state, in their desire to subjugate men,” read the tabloids.

Of course: before signifying emancipation, the miniskirt was seen as a mere erotic lure, as evidenced by the scanty outfits of comic book heroines and sci-fi movies and series of the fifties. “The pin-up with a miniskirt of the intelligentsia,” The Washington Post described Gloria Steinem after that Life magazine article in 1965, in which the activist discussed the ins and outs of the emerging pop culture. Another proof that the prevailing, predominantly male gaze on the garment was still external.

Today, it seems impossible to deny its politicization from the moment it hit the streets, inseparable from a social context in which women began to gain ground in the workplace and control of their reproductive health; however, its incorporation into the narrative of female economic, social, and sexual independence was not as early, although the coincidence in time with the commercialization of the contraceptive pill—available in the UK since 1961—aided the myth. “Women had been working on it for a long time, but before the pill, real independence couldn’t be possible. And when it finally happened, it was clearly reflected in the look, in the image of the moment, with an almost childlike exuberance that screamed, ‘Wow, look at me! Isn’t it wonderful?'” Quant referred to in that 1988 conversation.

Beyond moralistic considerations, the miniskirt was accused in its day of both objectifying women and embodying all the evils of capitalism. It was also accused of promoting thinness. Diet frenzy ensued with it, as did overproduction (the Ginger Group line had nearly 200 points of sale in its country alone), driven by a voracious demand that, for the first time in history, made clothing not meant to last (yes, complaints about the poor quality of clothes were frequent). In statements to the Sunday Telegraph in June 1966, Quant herself acknowledged that such frenzy might need to be calmed. And she promised a fall of culottes in return. What she offered instead was the microshort. “Once you’ve experienced the freedom in short skirts and low-heeled shoes, you don’t want to go back to restrictions,” she admitted. “The miniskirt is forever,” read the banners brandished by the self-styled British Society for the Advancement of the Miniskirt, the women’s command that protested outside Dior’s headquarters against the return of long skirts in the fall-winter 1966/67 collection of the French house.

Nothing and no one prevented the maxi skirt from asserting its law at the end of the decade. Relegated like any fashion product to the capricious ebb and flow of trends, the mini has reappeared in the female wardrobe with better or worse luck since then, a lycra body tube in the eighties, perversely naive in the nineties (the grunge kinderwhore dresses), impossibly brief in the 2000s (that “skirts should be the size of a belt: life is short, you have to take risks” from Paris Hilton), empowered by default a year ago (Miu Miu’s viral version, last fall-winter). But why does it seem to be the only thing that has transcended from Quant’s not insignificant legacy? Pay attention here, because, go-go boots, tight-knit sweaters (the skinny rib, the result of testing the Peter Pan charm of a boy’s sweater on her body), nylon tights in bright colors or prints, microshorts, and PVC raincoats aside, the designer also spearheaded the androgynous revolution of the pantsuit, of greater real impact in terms of emancipation for women’s dress. In the implicit sexual component of the miniskirt, a frosted cherry on top of that freedom, one may find the answer. Although that commercial genius who, by pressing the right key, not only made it ubiquitous but also necessary, explains it better. She herself pronounced the sentence: “A good designer is like a newspaper editor, staying ahead of the news, breathing what’s in the air.”